I’ve been thinking how to explain photographic optics to beginners, because the explanation is usually something like this: the bigger the sensor, the lesser the depth of field, the closer the point of focus the lesser the depth of field, the wider the aperture the lesser the depth of field, the bigger the focal length the lesser the depth of field. So, depth of field is inversely proportional to focal length, sensor size, and aperture, and directly proportional to focal distance.

But what exactly is the depth of field?

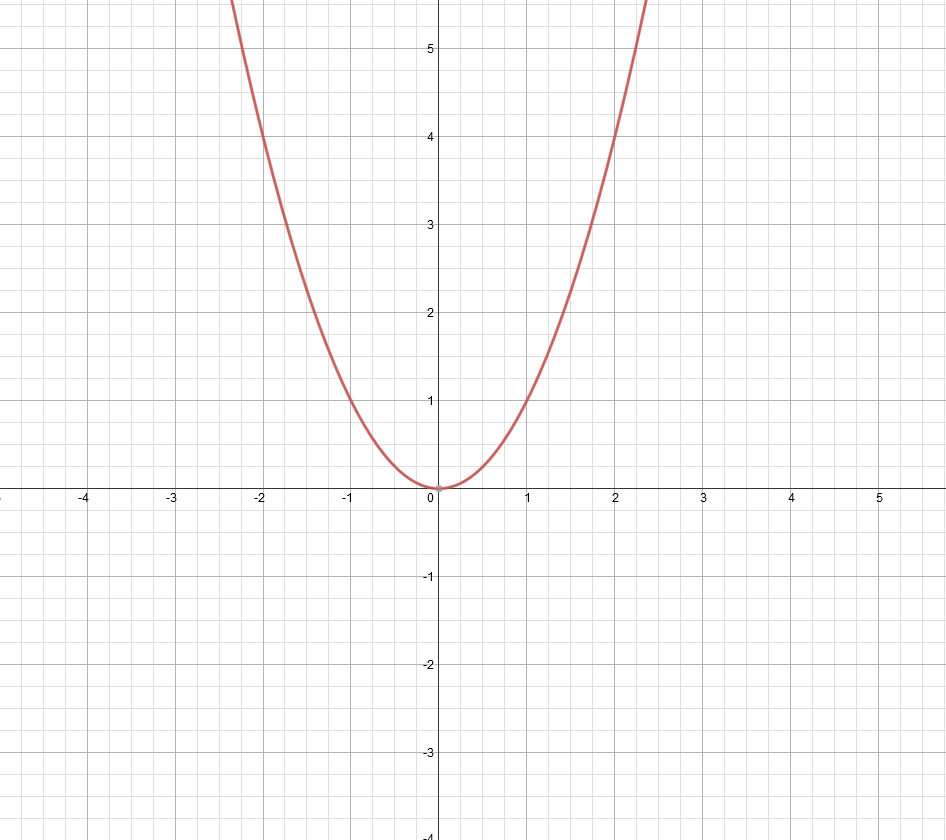

To understand depth of field, you need to understand that only a single point in the image, the point of actual focus, is perfectly sharp. Everywhere else, the lens diffuses a ray of light into a circle, called the “circle of confusion”. If the circle of confusion is small enough to fit into a single pixel on the sensor, basically if its diameter is less than the pixel pitch of the sensor, we perceive it as “sharp”. However, what it actually looks like can be mathematically represented as a parabolic function:

Let’s say that the x axis represents the distance from the focal plane of the sensor. 0 is the point in focus. The y axis represents the diameter of the circle of confusion, and 0 means that it is in perfect focus, and y is a mathematical point. If it’s below 1, it means it is perceived as sharp because the diameter of the circle fits within one pixel. So, everything between 0 and 1 is perceived as sharp, and as the radius grows, the picture starts getting blurry. Let’s illustrate this photographically:

As you can see on the asphalt, there is a tiny strip of sharpness, and everything before and after is blurry, progressively with the distance from the point in focus. At the most distant parts you can clearly see the circles formed as the rays of light are defocused. On the strip in focus, it appears that more than just a single point is in focus, because for some time the defocused circles are small enough to fit within a pixel on this level of magnification. This strip that is perceived as sharp is called the depth of field.

The shape of the circles of confusion beyond the depth of field is called “bokeh”. The angle of the parabolic function defines the amount of bokeh. If the parabolic function is steep, it means that only the things very close to the point of focus are sharp, as everywhere else the circle quickly grows into huge “bokeh balls”:

If the function is “shallow”, it means that it is possible to create an illusion that the entire image is sharp, from the closest visible point all the way to the horizon, because the diameter of the circle of confusion at the desired magnification of the output is still less than 1, or close enough not to matter:

So, in effect, the perceived sharpness beyond the point of actual focus is an artifact of magnification and photographic trickery. If you magnify enough, you’ll see that almost nothing is ever in perfect focus.

Now we get to the useful parts. If you shorten the focal length, you reduce the angle of the parabolic function, making it almost parallel to the x-axis. The same happens when you reduce the sensor size, but the reason is trivial – you need lesser actual focal length to produce the same field of view on a smaller sensor, so it’s still merely a function of the focal length. When you stop down the aperture, you force light to go through a smaller circle, reducing the cone of light that produces a mathematical point when in focus, or disperses more strongly when not. In theory, only a picture formed by perfectly collimated light source, meaning parallel rays of light, would be in perfect focus, meaning no light cones, but laser rays; also, this means that a pinhole camera, or a camera with a lens stopped down so extremely that it becomes a pinhole, would form a perfectly sharp image with an infinite depth of field. However, as the aperture becomes smaller, the rays of light interfere with its edges, which blurs the image, which means that such a perfectly sharp image would also become perfectly blurry due to diffraction. So, since, the f-stop is a function of the focal length, the absolute aperture is merely a function of the focal length as well, which means that we managed to reduce three parameters to one – sensor size, aperture and focal length are all functions of the absolute focal length, which leaves distance from the focal plane. However, if you imagine the light cone formed by the object in focus, it is obvious that the angle of this cone becomes larger as the object is closer, and smaller as it is farther. This means that the rays of light become closer to parallel as we focus closer to infinity, which produces an effect similar to stopping down the aperture. This also means that we managed to reduce all our parameters to the angle of the light cone, and diffraction as the second limiting factor that literally interferes with sharpness.

Sure, there are other optical effects that play a role – for instance, the difference in sharpness away from the centre of the circle that the lens draws, and within which the sensor is inscribed, the difference in refraction of various wavelengths of light, which creates chromatic aberration, the difference in the amount of light that falls on the edge of the circle relative to the centre, which defines vignetting, and so on. There are many optical defects that detract from the ideal appearance of the image, and although sometimes those optical defects can look interesting or charming, I personally subscribe to the opinion that less is more when it comes to defects. The only optical defect that I actually intentionally introduce to images at times is vignetting, because I think it focuses attention to the centre of the image, which is usually useful.

In any case, the difference between optical defects and optical laws is that the optical laws are something that will determine what happens with every single lens of a certain aperture and focal length, when projecting a circle of a certain size upon the focal plane. Optical defects, however, are what differentiates lenses of superior and inferior optical design and quality. This means that all telephoto lenses with wide aperture will create very shallow depth of field, but the good lenses will be tack sharp in the point of focus and devoid of significant defects, while bad lenses will be lacking in sharpness everywhere, and will introduce all kinds of optical defects, such as field curvature, low resolution, chromatic aberrations, colour cast and so on. Complexity of design and manufacturing tolerances that make a difference between bad, good and great lenses can be really extreme, which is reflected in the price; your tolerance for optical defects might vary. Unlike defects, the optical properties that are defined by focal length, circle size and aperture are universal, and don’t vary with lens design and price range.