No words.

(forwarded from IntelSlavaZ)

I think I can now properly explain why I think my old approach to spirituality was flawed, and why I replaced energy work and “shaktipat initiations” with theoretical explanations across several fields.

To quote myself:

“When I think about the limits of quantitative growth, the necessary conditions are in the ability to extend one’s ability to feel others, and the “cracks” and “discontinuities” in one’s spiritual body are usually due to faulty ideas and beliefs that basically limit what you feel you’re allowed to do, and what is “right”. Also, there is a real possibility of having your mind so open your brain falls out, so to speak, and by feeling compassion with someone who is wrong, you lose your own correct perspective and adopt the wrong one, and if you’re not skilled at juggling multiple viewpoints, you might actually degrade your spiritual body instead of expanding it, so that would be counterproductive. “

Basically, if one is close to actually being able to need and use spiritual help, the problems they would be having are of the kind that can be solved by abandoning faulty ideas and learning how to think, feel and let go of things properly. The energy part usually takes care of itself, but the increase in energy puts pressure on the “fault lines” within one’s spiritual body, and this creates the need to change one’s worldview and intellectual framework, and it’s useful if you’re shown how to do it. The worst cases of energy-related problems were in fact caused by refusing to let go of ideas that formed energetic blockages, and things can get really bad if you’re that stubborn – not letting go of Christ, Bible, Vedanta, materialism, Buddhism, your sinfulness or whatever it is you think you know for certain. One needs to allow God to rebuild his knowledge and beliefs, instead of having fixed points that anchor you to a certain place, creating energy blockages that are, fundamentally, opposition to allowing reality to sink in, because you love your placeholders too much. Allowing God to rebuild you means letting go of everything you think you know about God, because all of this is quite obviously false, because a non-enlightened person can by definition have no good ideas about God, because good ideas are all “pointers” to directly perceived realities, and a non-enlightened person has only the “plastic placeholders” in places where God should be, and those placeholders need to be removed in order for reality to sink in. God is infinitely better and more sophisticated than your religious ideas, and that is true regardless of your religion, so you need to become spiritually flexible, but not to the point of being an idiot. It’s a skill one needs to learn, and bad ideas in this area are great hindrances to spiritual growth. So, there you go.

robin wrote:

danijel wrote:

That’s all true, but the real question is, if “more self-realization” isn’t the path forward, explaining the difference between a rock and sudarshana-cakra, or a flower and the mind of Shiva, what is? Compassion, in the sense of “becoming more”, expanding what you are into the realm that is presently beyond you? That seems to be the closest, because, obviously, things like suffering and yoga might be side-effects and tools, not the working principle; for instance, when through compassion you expand to include non-self things, they are usually what Patanjali would call “disturbed”, they create terrible whirlpools of citta that emotionally translate as “suffering”, and then yoga comes to play, as means of working through the suffering and “thermodynamically” calming the spiritual substance, the way a compressor in a refrigerator “calms” the gas by extracting the excess heat. This seems to be the basic Buddhist explanation for the phenomenon of spiritual growth, and I can’t presently think of problems it doesn’t solve.

You wrote earlier that one needs to increase both size and quality of the spiritual body in order to grow spiritually. I assume compassion in the context you describe it here, will increase the size of ones spiritual body through the inclusion of additional kalapas after they are calmed and integrated. In this sense, compassion seems to be part of the equation, but something else would be required to increase the quality of the soul in addition to its size. If one uses compassion to acquire more kapapas and calms them to ones version of perfection, wouldn’t the mass increase but the quality remain the same? Its obvious to me that God is not just bigger and more powerful, it’s whole other level of quality altogether. So much so that I’m not sure one could arrive at something like that through incremental progression, that level of quality difference feels like a result of something else entirely that I appear to have absolutely no knowledge about. So what to do about the quality part?

That’s a good observation, and I would have to think about it for some time before coming up with a solid answer. At this moment I’m half-sick (Biljana is really sick, down with high fever and something that looks like flu, but I can’t exclude some covid mutation, and I seem to have the same virus but asymptomatic; either incubation or my immune system is dealing with it) so my brain isn’t in top form, but let’s see…

Things usually follow a pattern of quantitative growth, followed by a qualitative breakthrough, such as initiation into vajra; it doesn’t feel arbitrary, so there must be some kind of underlying physics involved – for instance, in order for a spiritual body to grow to a certain size, measured in number of kalapas, the structure needs to be pure/homogenous, or it will collapse/fragment. However, if you get to a certain size, meaning that you maintained sufficient purity, a process of qualitative transformation begins, the way a liquid would turn into a solid, or very highly compressed hydrogen plasma would undergo fusion in order to form helium. Subjectively, this transforms your spiritual states from the expectation of greater/purer love that would follow if the present conditions were extended quantitatively, to states of consciousness that exist on a fundamentally different coordinate system, to the point where human language barely has any words to express them, due to the fact that almost no humans ever entered those states of consciousness and verbalized them. Most of it is metaphor and imagery that works if one is “there” so he can see what you’re talking about, but it’s nothing human, and nothing one would expect, but it is the “universe” in which god-stuff exists, and you can finally get how some things are possible. But, I must admit I don’t have a strong theory explaining the conditions defining the limits of quantitative spiritual growth. Also, I don’t yet understand how the process maps onto physical incarnation; I seem to have passed through phases of spiritual growth in this life, such as initiation into this and that, and yet all it seemed to do is create bridges and interfaces between this body and the pre-existing spiritual entity that had all this and more. The mahayana explanation of bodhisattvas and their process of “incarnation”, in fact spawning tulpas, is the best I have so far; basically, a bodhisattva looks at this world, feels a need to do something, and the motivation takes form of a tulpa that is a physical being that has a very strong motivation to grow back to the original spiritual entity that spawned it into existence. The more I got initiated, the closer I became to being the full physical incarnation of my true being. The corollary, of course, is that you can have failed tulpas, beings that failed to close the circle and attain higher initiation.

As an addition, when I think about the limits of quantitative growth, the necessary conditions are in the ability to extend one’s ability to feel others, and the “cracks” and “discontinuities” in one’s spiritual body are usually due to faulty ideas and beliefs that basically limit what you feel you’re allowed to do, and what is “right”. Also, there is a real possibility of having your mind so open your brain falls out, so to speak, and by feeling compassion with someone who is wrong, you lose your own correct perspective and adopt the wrong one, and if you’re not skilled at juggling multiple viewpoints, you might actually degrade your spiritual body instead of expanding it, so that would be counterproductive. The underlying assumption is that growing your spiritual body after a certain “normal” point requires additional skill on multiple dimensions – more detachment, more ability to shift perspectives, more mental and emotional agility, where your emotions are not “sticky” and you can get in and out of them quickly, and you need to be able to let go of your worldview/religion if it is restrictive. Considering how people usually think their religion will take them all the way to perfection, being able to let it go after it proves restrictive and doesn’t allow you to go further is quite an obstacle. Basically, the extension of quantity even a little bit after the “normal” point introduces quite a bit of additional spiritual demands, and it is definitely not “business as usual”, or a monotonous grind until some arbitrary point where you converge with the requirements for a qualitative initiation. Also, at least parts of the experiences preceding vajra initiation seem to be caused by the processes taking place in your astral body as it converges towards the limits and its inner weaknesses are “compressed” by the physics of the situation, like you would expect gravity to compress matter towards the limit where a “hot Jupiter” becomes a star, or something becomes a neutron star. Basically, shit gets increasingly weird, and people usually experience lots of assistance from above during this period – there are tests you must pass, there are temptations, there are things you must face and overcome, and so on. I’m not sure it’s not just the physics of extreme pressure creating “dakinis“, to be honest, but the result is the same – there are tests, and one can fail; I’ve seen that happen, too.

robin wrote:

danijel wrote:

Compassion, as I conceive it, means to understand that it could be you in that “non-self” entity position, and when you are skilled enough in yoga, you can extend your area of “self” to engulf either a person and an object, and think and feel from their position, and if their understanding is flawed, you bring it to correct understanding by introducing proper arguments that improve thinking, and you apply yoga to the disturbances of your mind – because it is now your mind, since you expanded the definition of Self to engulf it – and process the karmic impurities that are now your own.

What if the person or object you’re extending yourself into doesn’t want to change, let go or alter their understanding?

Then you get my failed students. 🙂

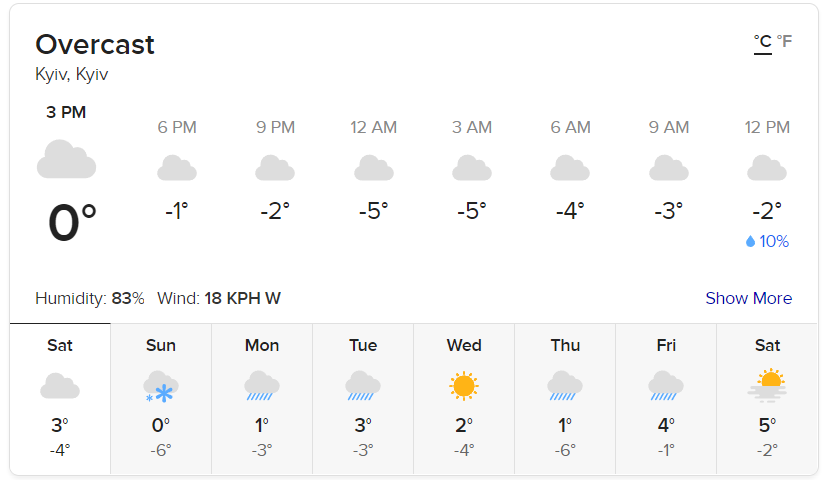

The ground is freezing in Ukraine, which means the Russians will attack, which means the end of Ukraine, which means the NATO/America will go in openly trying to seize at least the western part, which means there will be direct contact of Russian and American troops on the ground.

At the same time, collapse of the American stock market and the dollar is expected, and the central banks have something planned that seems to include revaluing the gold price in order for all who own it to be able to rinse their debt and inflation.

And yeah, I think I have a possible explanation for the Russian withdrawal from Kherson: it becomes obvious once you remember the old news, from when it was freshly liberated by the Russians. You see, a significant percentage of the population (20-40%, not sure) there are Ukrops, who hate Russia. The Russians withdrew all their guys into Russia proper, left the Ukrops there, and now their beloved banderistas from Kiev are recruiting them for cannon fodder, or torturing and killing them because they suspect them of working with the Russians. Also, no electricity, water, food or anything else there. I guess hatred for Russia will keep them warm.

All that is nice and lovely, you will say, but how can it possibly leave any room for economy, politics and war, which is all you seem to be writing about lately?

I would start by making a reference to the Bhagavad-gita, where Arjuna asks the same question – “If all that is true, why do you ask me to commit this horrible act, o Krishna?”. I would say that the contradiction and the apparent incongruity is, again, due to semantics, where “compassion”, “love”, “unity” and other words mean one thing to a yogi, and quite another to common humans.

To humans, dharma would mean some kind of “harmony” where there would be no violence or strife, and everybody would be happy. To a yogi, dharma is a state of living God, and if God takes a form of affirming something that is good, or a form of destroying something that is evil and stands in the way of virtue, it is all the same. People somehow make an assumption that God wants all souls to “be saved”, or “achieve Nirvana“. That formulation is not aligned with dharma. Dharma would mandate that brahman overcomes illusion, that virtue is chosen and manifested, that truth and greatness are lived and shown. To accelerate this process will mean to accelerate choice – to either be of God, or not to be at all. This, then, translates into politics – there are systems of organizing worldly life that promote dharma more or less, which means that one must favour the political systems that favour the correct principles. It’s the same with economy; the system that rewards goodness, utility, advancement of knowledge and promotion of dharma must be established and favoured, and economy that increasingly rewards dharmic behaviour, and punishes adharmic behaviour, is a manifestation of dharma. Basically, if someone creates wisdom, beauty, goodness and so on, he should be rewarded with money, so that he would have more energy to do more of that in the world, and, conversely, if someone does nothing good and useful, and uses whatever he has to make lives of others miserable and to oppose dharma wherever it is manifested, he should be punished and money be taken away from him, so that he would lack energy to do things in the world, and would eventually starve and wither. Obviously, it goes against the expectation that the manifestation of dharma would be some kind of communism, where everybody would be treated the same and have the same, just because brahman is One in all. That’s not how things work. Brahman is not just “One”. Brahman is also sat-cit-ananda, reality-consciousness-bliss. To live dharma is to promote sat-cit-ananda, and if something is hindrance to sat-cit-ananda, meaning it is of illusion, ignorance and suffering, it is to be removed from existence, and not treated equally as a manifestation of God, just because God is one. The expectation of equality is a fallacy. What needs to be applied equally is the criterion of manifestation of brahman; the results, however, will differ greatly, and the same Krishna will be friend to the good and virtuous ones, and death and destruction to the evil ones. God doesn’t create some kind of sheep heaven where lions and cows eat yoghurt together. As Arjuna rightly said to Krishna, “it is right and proper that all saints and rishis bow before you in reverence, and all the demons and evil-doers to run away from you in terror”.

To provide another perspective, let’s refer to the Augustinian concept of righteous war, which sounds like a contradiction, if you are untrained in thinking with any kind of layered complexity. You see, St. Augustine would say that God formulated certain laws, and one of them is “do not kill”. However, what happens when you as a God-loving nation are faced with an enemy that will kill you, given a chance? You need to try to dissuade them and show them the error of their ways; basically use diplomacy. If that fails, you need to scare and intimidate them, to show them the fatal consequences of war against you; this is deterrence. If that fails, you need to weigh the amount of good and evil that will happen along both options – to either wage war, or not. If a situation where you don’t wage war results in more good than evil, then you should surrender; this is the case if war is to be waged over some irrelevant dispute, and the enemy is not inherently evil and does not intend to enslave, murder and impose a godless order upon you, but instead wants access to some natural resource. The principle is that war should never be waged over such things, and they should instead be solved by diplomacy and commerce. If the enemy is inherently evil, however, and wants to prevent you from living in accordence with the will of God, if he wants to enslave you or murder people, then this should be opposed, and war is to be waged as effectively as possible in order for such a threat to be removed. At the very moment the threat is removed, however, violence should cease, and all efforts are to be invested in repairing the damage caused by the war. St. Augustine mentions the bad examples from Roman history, where the victors continued to murder people out of spite and vengeance after the war was over, instead of proclaiming peace. Obviously, even if you think that killing and violence are evil, and are forbidden by God, you are to stand in the way of people who intend to murder and commit violence and oppose the will of God, and if violence is necessary in order to defend peace, you better learn how to be good at violence.

Buddhist view of war is very Augustinian, because Buddhism doesn’t see ahimsa the way Jainism does, as a central virtue. To Buddhism, what matters is to promote dharma and metta, reduce suffering and accelerate liberation from samsara. Violence is seen as a knife – it is usually an instrument of evil, if it is used for killing and maiming people, but if it is used by a surgeon and as an instrument of healing, it is good. Ahimsa in Buddhism is an important principle, but if ahimsa means opposing and destroying adharma by violent means, so be it. What is common to Christians and Buddhists is that they would find it universally objectionable to mistreat prisoners of war or terrorize a conquered population: they would try to promote goodness and preach the right way, and if they are faced with someone who doesn’t want to change and learn, and is a danger to others when released, they would likely just kill him, rather than torture him by prolonged imprisonment. Making the utmost virtue out of life itself is a materialist thing, and is foreign to all religions that believe in a transcendental reality.

What separates Buddhism and Christianity is their position on suffering. To Buddhists, suffering is outright evil and should be prevented and opposed if at all possible. To Christians, things are more complex. Yes, suffering is not pleasant, but suffering is also good against arrogance, because they noticed that people tend to turn to God and abandon their arrogant and godless way when they are sick and in pain, and they actually introduced forms of self-torture as prevention/cure against arrogance and godlessness, and this is actually a form of spiritual practice in some monastic orders. Also, suffering of Christ had redeeming qualities. The Christians will therefore not see a great evil if torture is used as an instrument of teaching arrogant and evil people that they are not gods. My opinion is that this is fraught with too many dangers to be used effectively against evil, because both from the position of Vedanta, where actions that are not of sat-cit-ananda are to be avoided, and from the position of Buddhism, where suffering is evil and metta is recommended, any kind of torture and humiliation of others is to be seen as evil, and always avoided. Unteachable evil people that are a danger to others might need to be killed, but if you approach this by turning yourself into a monster similar or worse than those you are fighting, you are not manifesting dharma, you are finding excuse for indulging your sadism.